by Alan Moore

|

Art works have been disappearing around Staten Island this spring and summer, changing and vanishing in unexpected ways. It’s disconcerting if you think of art as something unchanging, made to be -- that should be -- there for all time. Of course this isn’t so. Contemporary public art has a lifespan, sometimes very brief.

The first to go was a mural painted by Kristi Pfister two summers ago on a building on Clove Road. Her mural, funded by COAHSI, depicted the houses of the street seen in earth-toned profile above a cross-sectioned street imagined deep into the earth, revealing rocks, bones and skeletons. Pfister's mural was “gone over'” in late spring by a commercial sign painter. Of course this swift suppression of a work conceived for public enjoyment in favor of another directed at the getting of money demonstrates overt contempt for public art. It is a classic case of art versus commerce where, as we know from this central myth of our culture, art loses. The story is a little more nuanced, however. Yes, the mural was wiped out by a graffiti-style painter’s advertisement for a tattoo parlor. But a key image in Pfister’s pictorial meditation, a 17th century Dutch colonial house, has been retained in the new design. There is then a token recognition of the site of the public mural and an aspect of its imagery in this work-for-hire by an aerosol artist that makes the commercial sign “artful”, that is, knowing of itself in its being. Aerosol art -- “graffiti” -- is the most contingent and ephemeral of mural styles, often no sooner put in place than wiped away. Tattoo, the commercial art advertised by the sign, is also necessarily ephemeral, limited to the lifetime of its `canvas,’ and well before that span is reached, feathering away into an illegible blur of ink-stained skin. Both artforms, graffiti and tattoo, have been traditionally linked with aggressive trespass, crime and the life of the underclass. Tattoo has only recently been legitimized as a cosmetic practice, and indeed allowed as a business. Likewise, graffiti-style aerosol art has only a tenuous foothold in commerce as a genre of sign-painting. So this incident of disappearing art evidences not only the clash of art and commerce but the clash of two image cultures in public art. One is imbued with ideals of permanence and change; Pfister’s mural itself was a meditation on the obliteration of humans and their creations with the passage of time. The other is wedded to the moment of its creation -- it shines briefly and disappears. |

|

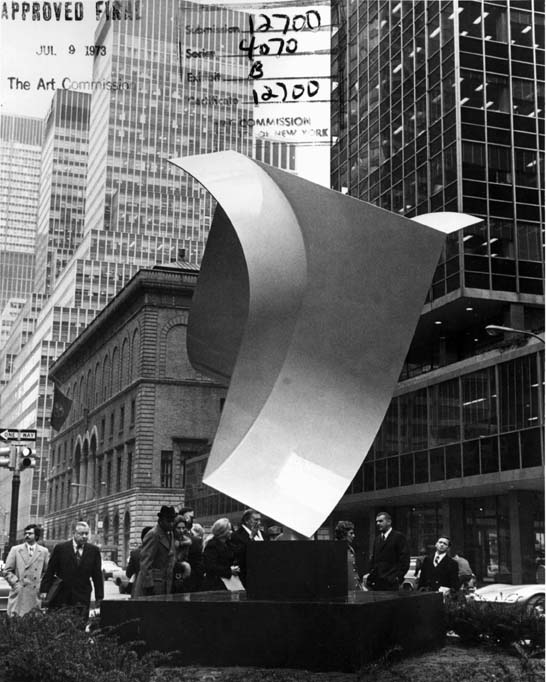

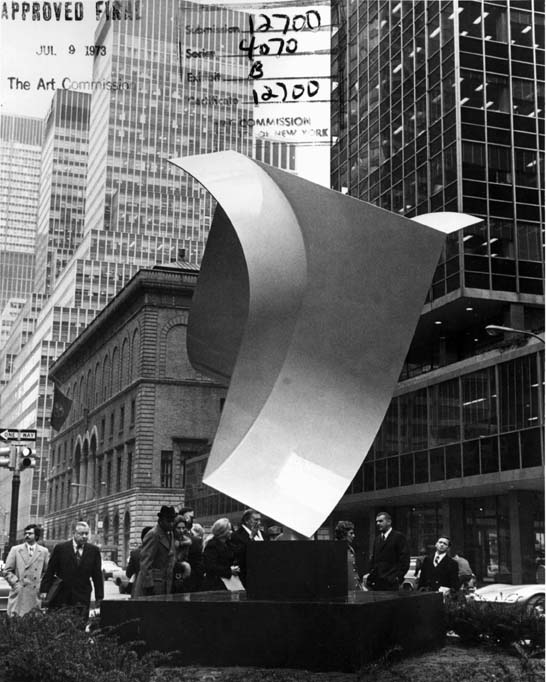

Untitled No. 1 vaguely resembled a piece of nautical equipment, like the old anchors and capstans that stud the asphalt along our gradually renovated waterfront promenade. The piece, however, had not even the glamor of historical association that these relics possess. It is (was) an artwork with a nautical air; this hunk of white-painted steel might have been torn from Corbusier’s Villa Savoy. The work in any case was entirely abstract. This diminishes its reality as art in the eyes of most casual observers (although to some it enhances it).

How did Untitled No. 1 come to be there in the first place? No one seems to know. This artwork stood at the end of the taxi ramp of the ferry terminal as if in aesthetic witness to the mentality of the builders of the approaches to the St. George terminal. This obstacle course is built entirely for machines, as if robots were riding the ferry every day, spit out directly into trains and cars without any need to convey themselves by foot. The kind of abstraction that informs Untitled No. 1 however, was born of utopian ambitions, ambitions that inform the design of the terminal itself. It stood as an emblem of the new future, a future where humankind would move about swiftly and surely in cars on broad new highways. Poisoned air, and communities vanished or trodden by roads suggest that the cost of this vision has been high. Untitled No. 1 was like an emblem of the terminal itself, a functional hub of transport symbolized by a sculpture that evokes some zone of function within a system of pure geometry. Bright white with clean lines both squared off and rounded, Untitled No. 1 only came to stand for -- and thereby to resemble -- a glorified cul de sac, a rat trap stood on end that is the St. George ferry terminal itself. Daily I pass through St. George terminal and then Grand Central, the one depressing, confusing, physically and mentally straining, the other lofty, grand and inspiring. The classically conceived Beaux Arts tradition of the 19th century is slowly being revenged over the cut-rate utilitarian mode of our mid-century. Now Untitled No. 1 is gone, while still the figure of an ancient Greek, cast in enduring bronze, points down toward the terminal from its perch just east of Borough Hall. If a sculpture no one much cared for has been disappeared, perhaps it is not everyday philistinism, but a token of resistance to the very idea of the terminal which Untitled No. 1 had come to represent. By disappearing its emblem, its token, perhaps the terminal can be -- better than merely renovated -- reimagined . . . Of course this is fantasy. The sculpture has been replaced by nothing. The terminal has simply been tidied up. |